Paul Moody (May 23, 1779 - July 5, 1831)

Paul Moody was a textile machinery inventor born in Byfield, Massachusetts. Working with Francis Cabot Lowell, he assisted in creating the first functional power loom in the United States. This loom was adapted from British technology and could turn cotton threads into finished fabrics at fast speeds. He also pioneered many additions to the machines, including the “dead spindle,” “filling frame,” and the “double speeder.”1 In 1828, Moody created a system that used leather belts and a pulley system to transfer power from a main shaft down to hundreds of connected machines. This innovation allowed for a smoother and more efficient transfer of power with fewer breakdowns.2

Paul Moody was a textile machinery inventor born in Byfield, Massachusetts. Working with Francis Cabot Lowell, he assisted in creating the first functional power loom in the United States. This loom was adapted from British technology and could turn cotton threads into finished fabrics at fast speeds. He also pioneered many additions to the machines, including the “dead spindle,” “filling frame,” and the “double speeder.”1 In 1828, Moody created a system that used leather belts and a pulley system to transfer power from a main shaft down to hundreds of connected machines. This innovation allowed for a smoother and more efficient transfer of power with fewer breakdowns.2

While in the city of Lowell, Moody opened the Lowell Machine Works to supply the city’s mills with these revolutionary machines. He served as the chief engineer for the Proprietors of the Locks and Canals Company and was the first resident of what is now the Whistler House Museum of Art in c. 1825, living there until his death in 1831. His ingenious inventions pushed the United States into a major leader in the textile industry, and the City of Lowell named Moody Street in his honor.

George Washington Whistler (May 19, 1800 - April 7, 1849)

Major George Washington Whistler was a prominent engineer who graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He was commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Artillery as a topography engineer in New York, later joining the Board of Civil Engineers working on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Major George Washington Whistler was a prominent engineer who graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He was commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Artillery as a topography engineer in New York, later joining the Board of Civil Engineers working on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

In 1834, Whistler moved to Lowell to work for the Proprietors of the Locks and Canals. Whistler was the Superintendent of the Lowell Machine Shop and oversaw the creation of the shop’s first locomotive in 1835. He disassembled an English locomotive and used the parts to create a pattern for one of New England’s first locomotives.3 After his time in Lowell, Whistler was the Chief Engineer of the Boston & Albany Railroad between 1840 and 1842, laying a route through the rough terrain of Western Massachusetts.

In 1842, Whistler was invited by Czar Nicholas I to construct a railroad connecting St. Petersburg and Moscow.4 Unfortunately, Whistler died in 1849 of cholera, two years before the completion of the rail line. However, the engineers of the St. Petersburg-Moscow Railway honored Major Whistler by commissioning a silver samovar (Russian teapot) as a gift to the Whistler family. The samovar is now part of the WHMA collection.

Anna Matilda McNeill (September 27, 1804 - January 31, 1881)

Anna Matilda McNeill was born in Wilmington, North Carolina. In 1831, she married George Washington Whistler, who was a friend of her brother. The couple had five sons together, although only two survived until adulthood. She travelled to Russia with her husband in 1842 and would return to the States after his death. She lived in Stonington, Connecticut and moved south to Virginia following the start of the Civil War to care for her son, William.

Anna Matilda McNeill was born in Wilmington, North Carolina. In 1831, she married George Washington Whistler, who was a friend of her brother. The couple had five sons together, although only two survived until adulthood. She travelled to Russia with her husband in 1842 and would return to the States after his death. She lived in Stonington, Connecticut and moved south to Virginia following the start of the Civil War to care for her son, William.

In 1863, Anna Whistler moved to London to live with her eldest son, James McNeill Whistler. During this time, James painted the famous portrait Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Artist’s Mother.5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (July 11, 1834 - July 17, 1903)

James McNeill Whistler was born on the second floor of the Whistler House in Lowell on July 11, 1834. In 1842, the family moved to Russia where James studied drawing at the Imperial Academy of Science. While he was staying in England due to health concerns, his father died of cholera. As a result, the family returned to America and lived in Connecticut. Here, James enrolled in the Military Academy at West Point, but was later dismissed and began pursuing art.

James McNeill Whistler was born on the second floor of the Whistler House in Lowell on July 11, 1834. In 1842, the family moved to Russia where James studied drawing at the Imperial Academy of Science. While he was staying in England due to health concerns, his father died of cholera. As a result, the family returned to America and lived in Connecticut. Here, James enrolled in the Military Academy at West Point, but was later dismissed and began pursuing art.

The artist spent most of his time studying in Paris and London and adopted his mother’s maiden name in his butterfly monogram (JMW).6 In 1877, Whistler exhibited his Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket at the Grosvenor Gallery in London. The painting was denounced by critic John Ruskin and blamed Whistler for “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” A trial for libel followed in which Whistler won, claiming that the painting was meant to evoke an experience and feeling rather than a time and place. He would continue to discuss his artistic theory in his Ten O’Clock Lecture in 1885 and The Gentle Art of Making Enemies in 1890.

From his theories, the beginning of the modern art movement would unfold. Artists began focusing on creating art for its beauty in the Aestheticism movement as well as incredible compositions of color in the Tonalism movement. Both of which can be wonderfully attributed to Whistler’s advocacy for “art for art’s sake.”

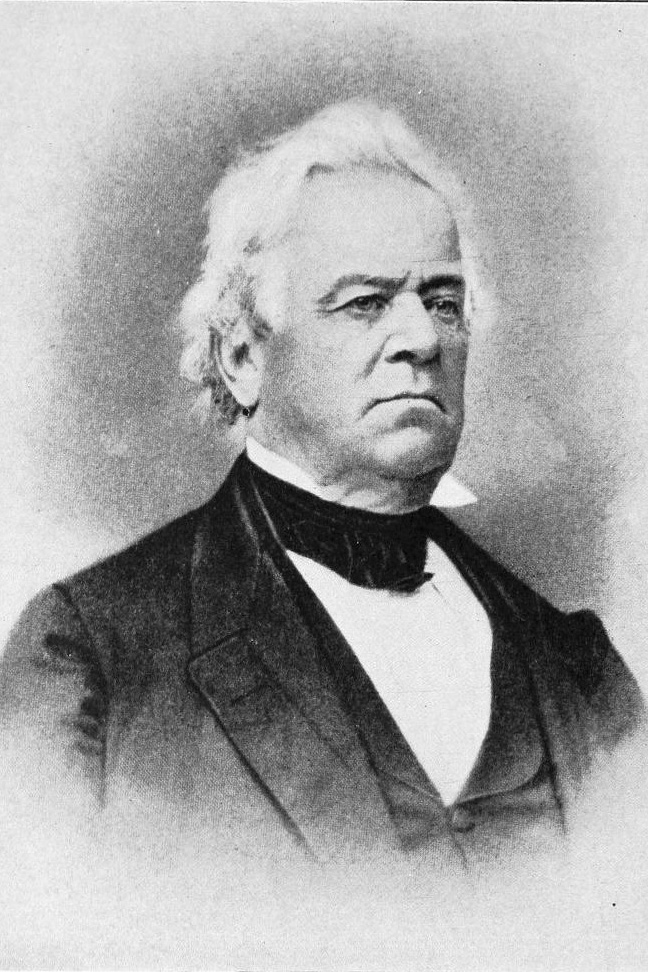

George Brownell (August 9, 1793 - April 27, 1872)

George Brownell was the successor to Paul Moody as the Superintendent of the Lowell Machine Shop (formerly the Lowell Machine Works). In 1836, he moved to Worthen Street after the Whistlers left. During his time, the expansion of the railroad was a major boon to the city. As a result, the Lowell Machine Shop built locomotives in addition to supplying looms to mills. He retired from the role in 1846 but continued his involvement in the growth of Lowell. On February 13, 1849, Brownell left Lowell to travel to England to inspect English railways and “study the industrial and mechanical conditions and methods.”7 As a successful predecessor of industrialization, many visitors would come to Great Britain to study the English model. Brownell wrote detailed descriptions of machinery and locomotives in his journal which he brought back and published in the United States. These details provide magnificent insight into the innovations being made in England.

George Brownell was the successor to Paul Moody as the Superintendent of the Lowell Machine Shop (formerly the Lowell Machine Works). In 1836, he moved to Worthen Street after the Whistlers left. During his time, the expansion of the railroad was a major boon to the city. As a result, the Lowell Machine Shop built locomotives in addition to supplying looms to mills. He retired from the role in 1846 but continued his involvement in the growth of Lowell. On February 13, 1849, Brownell left Lowell to travel to England to inspect English railways and “study the industrial and mechanical conditions and methods.”7 As a successful predecessor of industrialization, many visitors would come to Great Britain to study the English model. Brownell wrote detailed descriptions of machinery and locomotives in his journal which he brought back and published in the United States. These details provide magnificent insight into the innovations being made in England.

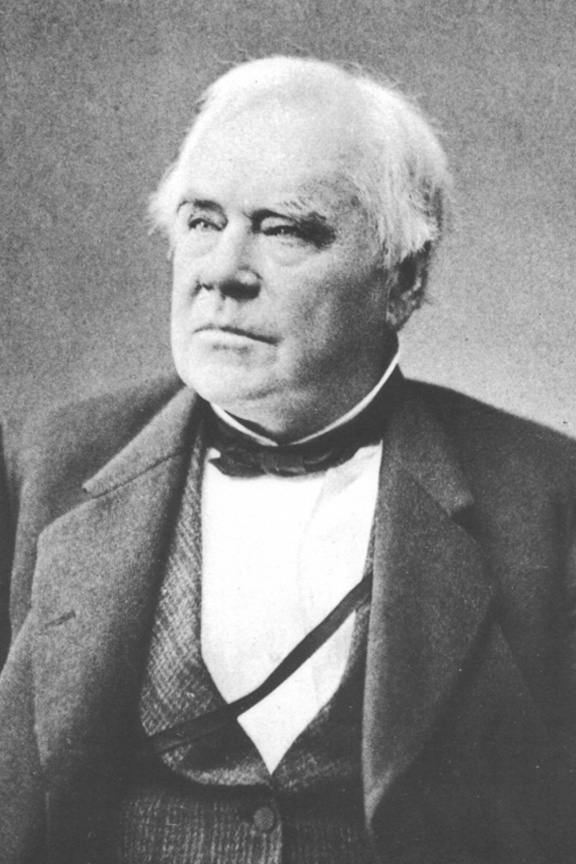

James Bicheno Francis (May 18, 1815 - September 18, 1892)

British-born James B. Francis was the son-in-law of George Brownell and well-known for his innovations in hydraulic engineering. Francis left England for the United States in 1833 to assist George Washington Whistler construct the Stonington Railway in Connecticut.8 The two men moved to Lowell in 1834 where Francis remained an assistant to Whistler, who was the chief engineer of the Proprietors of Locks and Canals at that time.

British-born James B. Francis was the son-in-law of George Brownell and well-known for his innovations in hydraulic engineering. Francis left England for the United States in 1833 to assist George Washington Whistler construct the Stonington Railway in Connecticut.8 The two men moved to Lowell in 1834 where Francis remained an assistant to Whistler, who was the chief engineer of the Proprietors of Locks and Canals at that time.

When he left Lowell for Russia in 1842, Whistler appointed the young Francis as his successor. James B. Francis began innovating ways of managing Lowell’s waterways to increase water flow while also revolutionizing the turbines used to generate power to the mills. Adapting a design by Uriah Boyden, Francis was able to redesign the turbine to achieve “an astounding 88 percent efficiency rate” compared to the 65 percent rate of the previous waterwheels.9 Further experimentation would create the “mixed-flow reaction turbine,” which would become the standard in America and be named the “Francis turbine.”10 Twenty-two of these turbines are still in the Hoover Dam! Francis published his work on hydraulic engineering in The Lowell Hydraulic Experiments in 1855.

1 Henry Adolphus Miles, Lowell, as It Was, and as It Is (Powers and Bagley and N.L. Dayton, 1845), 225-227, http://archive.org/details/lowellasitwasan00milegoog.

2 “Suffolk Mills Turbine Exhibit,” National Park Service, October 7, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/suffolk-mills-turbine-exhibit.htm.

3 National Park Service, “Lowell Machine Shop,” National Park Service, February 26, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/photosmultimedia/machine_shop.htm.

4 “George Washington Whistler,” American Society of Civil Engineers, accessed June 21, 2023, https://www.asce.org/about-civil-engineering/history-and-heritage/notable-civil-engineers/george-washington-whistler.

5 “About Whistler’s Mother,” accessed June 28, 2023, https://www.clarkart.edu/microsites/whistlers-mother/about/exhibition-(3).

6 “James McNeill Whistler - Biography,” National Gallery of Art, accessed June 28, 2023, https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1974.html#biography.

7 George Brownell, “The Journal of George Brownell on a Voyage to England in 1839,” in Contributions of the Lowell Historical Society, vol. 2 (Lowell, Mass.: Butterfield Printing Company, 1926), 324-25, http://archive.org/details/contributionsofl03lowe.

8 “James Bicheno Francis,” Britannica, May 14, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Bicheno-Francis.

9 Lowell National Historical Park and National Park Service, “James B. Francis,” Educational, National Park Service, May 8, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/james-b-francis.htm.

10 Lowell National Historical Park and National Park Service, “James B. Francis.”